Castle Square is a space in the city centre that we’ve all walked through, stopping maybe to sip a coffee or even eat our sandwiches, but how many of us are aware of its long history?

The site we see today was created in 1994 as part of an urban renewal project to provide a civic space that acts as a focal point and meeting place in the heart of the city centre. However, the location has been the setting for a number of significant events.

In this short trail we will look around Castle Square, examining the plaques located at the entrance to the square, depicting six of the historic events associated with the site, and based on drawings done by Swansea primary schoolchildren and were prepared by the artist Helen Sinclair.

We know very little about this period. However, the land rose sharply from the area at the Strand before falling away more gradually to the area west of Worcester Place. The site of Castle Square at that time was somewhat more elevated than it is today.

The first timber fortification was located at Worcester Place, the area behind Pizza Express, on the high ground adjacent to the original course of the River Tawe (the river here later became the North Dock, which was filled-in after World War Two). The timber castle was rebuilt in stone at the end of the 12th century, while another stone castle “The New Castle” dates from the 13th century when the outer walls of the castle were extended to incorporate the area that is now Castle Square. All that remains today is part of the new castle and several retaining walls next to the Strand.

By the 12th century, Castle Square was part of the Norman settlement lying just outside the palisade of the castle. It would probably have been covered with burgage plots and housed a small community of Anglo-Norman craftsmen and merchants who could withdraw into the castle if threatened.

In the 13th century the castle was extended and Castle Square came within its outer ward, being protected by a stone wall.

In the 13th century the castle was extended and Castle Square came within its outer ward, being protected by a stone wall.

The area was subjected to attacks by the native Welsh on numerous occasions, most notably:

At Swansea Castle in February 1306, three royal judges held a major court of inquiry into the activities of the Lord of Gower, William de Breos III. In the 1290s, de Breos had been involved in a number of disputes with the Bishop of Llandaff and the King, but from 1300 there was also a series of complaints from the tenants of Gower over de Breos’ misgovernment of the Lordship of Gower. So serious were these complaints that they were even raised in several successive parliaments. De Breos had acted as a ‘robber baron’ oppressing his tenants by falsely imprisoning them, forcing money loans, denying them proper justice in his courts, and coercing them to abandon legal actions against him. William de Breos issued two charters redressing these grievances and granting privileges. The Swansea Charter of 1306 is a major source for the history of Swansea in the Middle Ages and contains the earliest reference to coal mining in the area.

In 1326, Swansea Castle briefly became the centre of Edward II’s royal administration. In the autumn of that year, Edward, seeking to avoid capture by his estranged queen, Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer, fled to South Wales. By early November, he was at Neath, beseeching the men of Gower to come to his aid, and his Chancery and Exchequer were sent to Swansea Castle for safety. However, he was captured by his enemies and sent to Berkeley Castle where he ultimately met a violent end. The records and treasure left behind a Swansea Castle were subsequently pillaged by the locals, the enormous sum £13,000 being lost. A series of royal inquiries were subsequently held at Swansea to discover the guilty persons, but much of the treasure was never recovered.

The Plas, or Manor House, was a major feature within the area for many centuries. Its construction began in 1383, when John de Horton began to develop a plot which he had acquired within the castle’s outer ward. The building was extended over several centuries, and completed by his descendant, Sir Matthew Cradock, at the end of the 15 century. Sir Matthew died in the Plas in 1531, and the house descended through his daughter to the Herberts, who held it until 1740, when it came into the possession of Calvert Richard Jones. He lived there until his death in 1781. The Plas was demolished in 1840, when several coins dating from the reign of Edward II were discovered there.

Started in 1585, this was a stone building of two storeys, with its main accommodation on the first floor. The Guildhall/Court Room was at the northern end und the Grand Jury Room was at the southern end. The ground floor was used for a variety of purposes: store rooms, a gaol, and a weighing house. The town stocks were situated outside its main entrance. The building was the centre of local government and justice until it ceased to be the Guildhall in 1829, when a new Guildhall (now the Dylan Thomas Centre) at Somerset Place was opened.

During the Civil War, Swansea, which was originally Royalist, came under attack from the forces of Parliament and was captured in 1615. To prepare for the town’s defence, the Corporation, in 1642 spent £15 16s 9d on the construction of a gunpowder magazine on the ground floor of the Guildhall.

In 1684, Robert Wilmott of Gloucester, leased part of the new castle from the Duke of Beaufort, and set up a glassworks there, which he ran with his partner, John Man of Swansea. The lease refers to… ‘that parte of the Castle of Swanzey which hath been lately converted into a Glasse house’. It mainly manufactured bottles, which were used locally and which were also exported in huge quantities to Cork, in Ireland.

In the course of his career, John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, came to Swansea on several occasions to preach, and he had a long connection with the Plas House and its owner, Calvert Richard Jones. Wesley knew the Plas well, having visited it on many occasions after 1741. In 1760 Jones permitted him to preach in the courtyard of the Plas.

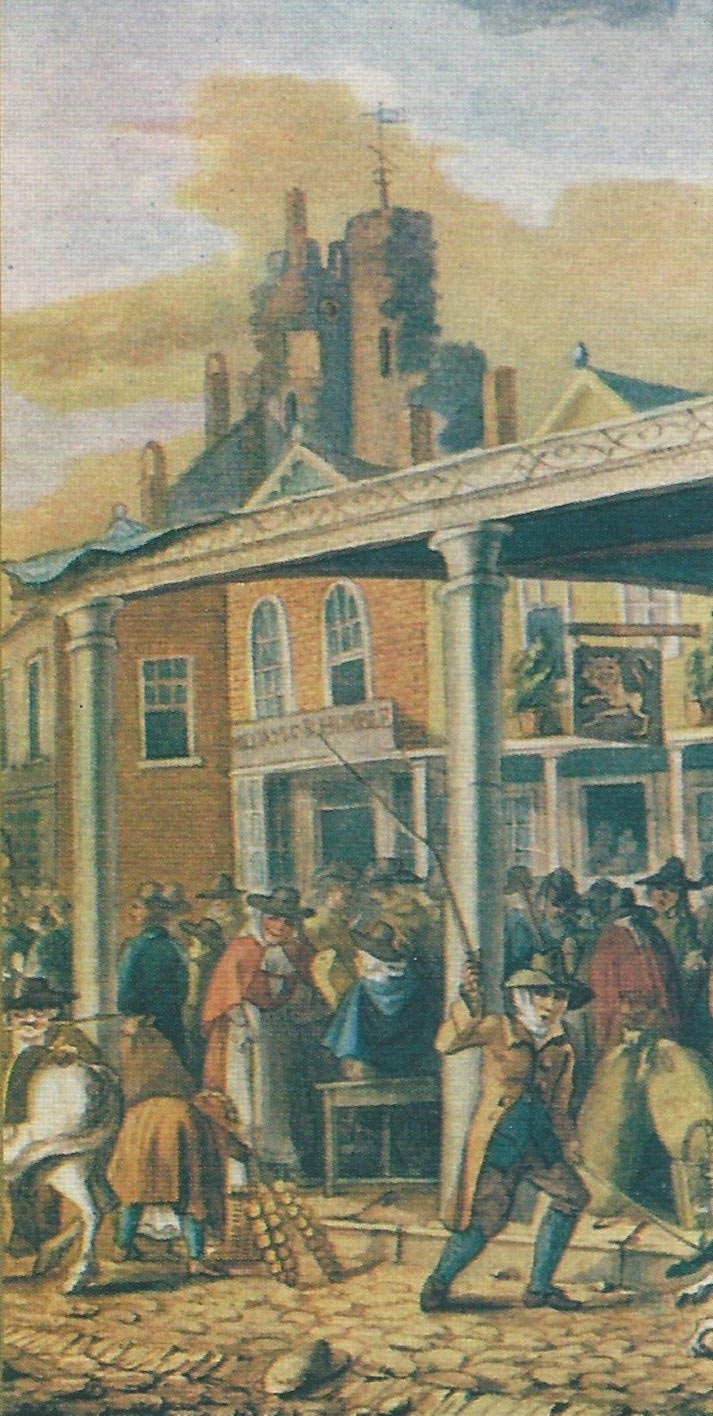

In 1773, the corporation decided to establish a new shambles or meat market, since the butchers’ stalls in the street around the castle were a nuisance and health hazard. In 1774, an Act of Parliament was obtained and the shambles were erected in the castle garden behind the Tudor Guildhall. Its cramped site made the shambles very unpopular both with traders and customers and it proved to be a dismal failure.

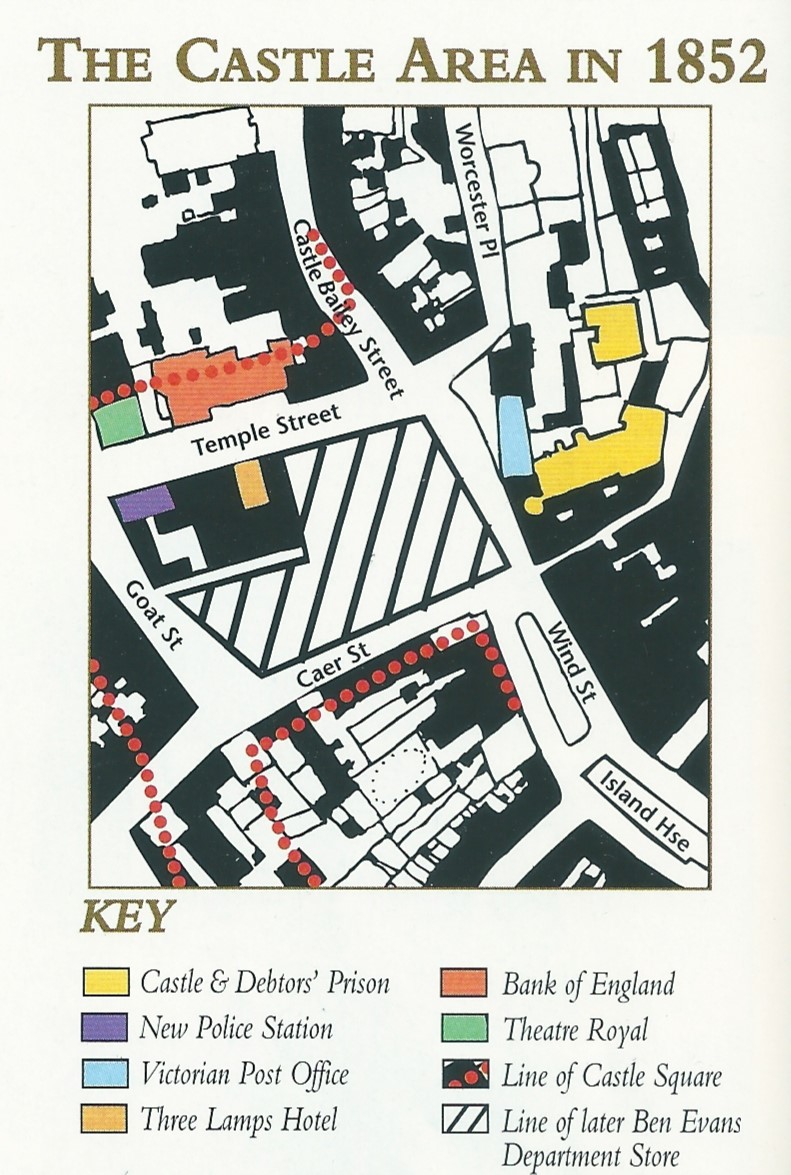

The name is a poetic reference to the Theatre Royal that was established in the first decade of the 19th century. There had been an earlier theatre, but in 1801, first discussions began about the possibility of erecting a new theatre of grandeur, more in keeping with the town’s status. Shortly afterwards a Tontine society was formed with the express intention of building a new theatre, and construction works began in the later months of 1806 on a site on the corner of Temple Street and Goat Street, where Zara is now. The new theatre opened on 6th June 1807. Its first manager was Andrew Cherry, a celebrated Drury Lane dramatist. The company that he ran included the renowned actor Edmund Kean. A later manager was William McCready father of the great tragedy actor W.C. McCready. Toward the end of the 19th century the theatre came under increasing pressure from Music Hall, as the most popular form of mass entertainment, and audiences declined. It was demolished in 1889.

In October 1826, the Bank of England opened a branch on Temple Street, as a result of lobbying from local industrialists. Both Cardiff and Merthyr had bid for the branch, but Swansea succeeded in getting it. The bank was sometimes referred to as the Glamorgan Bank. The branch had many years of successful trading, but in the 1950s it began to decline. In 1859 it closed, and its business was transferred to the Bristol branch.

In 1836, the Swansea Borough Police Force was established, and in the same year, part of the Tudor Guildhall was converted into the town’s first police station. In the 1840s Chief Constable William Rees caused a new police station to be built on the corner of Temple Street and Goat Street. This served as the force’s headquarters until 1874, when a new police station was erected at Tontine Street.

In 1856, the Tudor Guildhall was demolished to make room for the construction of a new head post office to replace the existing one in Fisher Street. The new building was opened in 1858, having been built of Pennant sandstone in the Tudor Gothic style to the design of an architect named Bayliss. In 1867 a clock was provided for the hitherto unadorned clock tower. The building ceased to be a post office in 1900, its main use thereafter being to house the offices and presses of the local newspaper company. It was damaged by incendiary bombs in February 1941 and was finally demolished in 1976.

Wales’s first large department store, Ben Evans & Co, dominated the site of the present Castle Square. Ben Evans, originally a Carmarthenshire farmer, had a small shop on part of the site in the 1870s. Gradually, his firm acquired most of the block and opened their gigantic store in 1894. The store became an institution synonymous with Swansea and its destruction during the Three Nights’ Blitz in 1941 was a great loss.

Situated on the south side of Temple Street and dating from the early 19th century, the Three Lamps was a well-known pub in Swansea, its name immortalised in the works of Dylan Thomas, who referred to it in two of his works. In Portrait of the Artist at a Young Dog, the young Dylan met Mr Farr there to begin their pub-crawl, while a character in Return Journey recalls Dylan ‘lifting his ikkle elbow in the Three Lamps’.

Cattle Square was in the middle of that part of central Swansea which suffered during the bombing raids of the three consecutive nights of 19th, 20th and 21st February 1941. Most of the buildings then located in Castle Square were razed to the ground, many by fires started by incendiary bombs, though some were destroyed by high explosives. Before the raids, the buildings standing there had been elegant Victorian and Edwardian structures which reflected the wealth of Swansea in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In all, forty-one acres of the town centre was devastated and casualties amounted to 230 dead and 409 injured.

In the immediate post-war period, the Castle Square area was cleared of bomb-damaged buildings and devastation, the Council deciding that it should be kept as public space. A scheme of paths and ornamental flowerbeds was opened in June 1953, in time for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The area remains today as one of the city’s public open areas with its seating, fountains and landscaping providing a major public meeting and recreational area besides the remains of the Norman castle.